18

Architecting Your Brand

As the beer industry continues to mature, we’ve worked with dozens of breweries who are opening a second, third or fourth location. We’ve seen this manifest as satellite taprooms or purpose-built production facilities. We’ve seen breweries start hard seltzer and/or cold-brewed coffee brands, distilleries, restaurants, food trucks, music venues, event centers and even hotel concepts. These leaps present complicated decisions to be made.

Do we use our brewery name on this new location or make it more tailored to its new neighborhood? If we want to open a new food concept, should we use our brewery name? Or does that even make sense if we’re not brewing there? Brand architecture will help you to answer these types of questions.

Your brand architecture is the framework you use to determine how all of your brands, current and future, interact with each other—how do specific brands relate or differ, how are they positioned and named, how are they priced, and how does all of this help you build your business? You may be thinking, “Why do I need to think about this if I just opened a brewery to make beer?” If the last few years of the craft brewing industry are any indication (with breweries making everything from seltzer, kombucha, cold brew coffee, and all manner of other non-beer items), I would encourage you to think about what the next three to five years could bring for your brewery.

Here are a few approaches to framing your brand architecture that you should consider as you think about expanding your portfolio.

Branded House

A “branded house” architecture centers around a strong parent brand that lends its name to all of its products. In this case, a brewery’s products support the parent brand without each having its own unique identity. This type of architecture is the most common approach breweries come to market with because it helps to build a strong overall brand that will lend trust to subsequent releases.

Branded House example: Prost Brewing out of Denver, Colorado uses their corporate name followed by a style for all beer releases (no fanciful names): Prost Pilsner, Prost Dunkel, Prost Weissbier, Prost Kölsch, Prost Kellerbier, etc. Their satellite taproom and production brewery bear the Prost name as well. This consistency creates a strong footprint as they continue expanding.

House of Brands

A “house of brands” architecture features a less prominent parent brand or one that falls to the background entirely to enable individual brands to stand on their own without any direct ties to the parent brand. Traditionally the stock and trade of mega corporations like Procter & Gamble and Unilever, this can be a valuable concept for craft breweries to employ as well depending on their product mix.

House of Brands example: AB InBev owns Budweiser, Bud Light, Corona, Goose Island, 10 Barrel, Golden Road, Breckenridge, Wicked Weed, Elysian, Devil’s Backbone and dozens of other breweries. While these breweries all run under the management principles and scale-minded growth plans found in Big Beer, as far as the customer is concerned, they all appear to be distinct brands, each with their own branding and IP (while competing with other brands at every price point and location). Ahh, the illusion of choice!

Here’s an example that may be more applicable to smaller breweries who don’t wheel and deal in mergers and acquisitions on a daily basis.

- Big Lug Canteen opened as a popular Indianapolis brewpub.

- Three years later, they opened Liter House, a Bavarian brewpub concept with an onsite production brewery.

- This allowed them to start canning beer under the ‘Big Lug Brewing’ banner.

- Then, they opened Half Liter, a Texas BBQ and German beer garden concept adjoining the Liter House concept.

If they had branded everything Big Lug, they would’ve confused customers and appeared to compete against themselves since all of these concepts sit a few miles away from each other. By creating stand-alone brands—Big Lug Canteen, Liter House, Half Liter, Big Lug Brewing)—Big Lug was able to evolve into Big Lug Hospitality, a house of brands that allows all their concepts flourish on their own.

Big Lug Hospitality uses a “House of Brands” brand architecture.

Using Brand Architecture to Grow Your Brewery

Your brewery will eventually have the opportunity to grow your footprint through internal product extensions or external partnerships. Let’s discuss a few different approaches so you understand the pros and cons of each and the broader implications they can have for your parent brand.

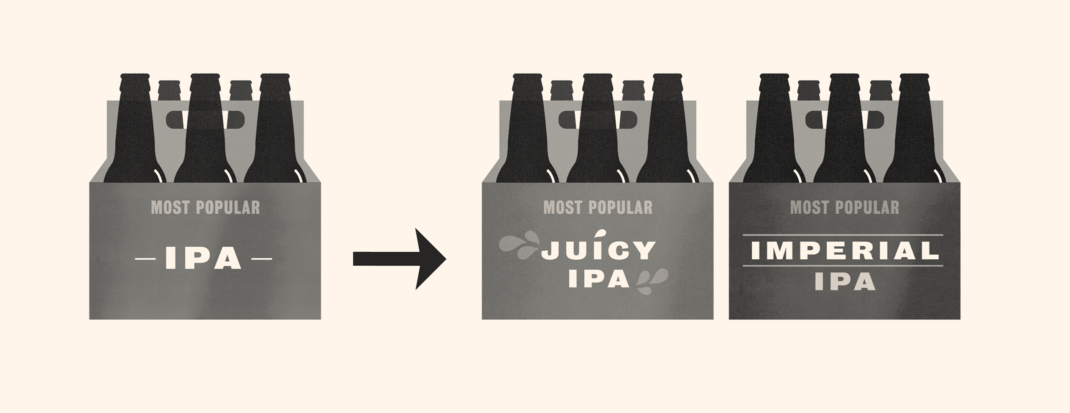

Line extensions

A line extension lends its established brand-specific name to another product within the same category (beer A begets beer B).

Example: “Fat Tire Amber Ale” and “Fat Tire Belgian White” or “Voodoo Ranger” and “Voodoo Ranger Juicy Haze” and “Voodoo Ranger Imperial Black IPA.”

New brand rollouts can be expensive for any brewery, but more so for regional and national players. By the time you’re through the package design process (including design fees, registering new trademarks, printing thousands of cases, cans, and bottles) and planning your on and off-premise product launch, you can be looking at a staggering number. And this still doesn’t count the time and treasure that goes into refining the beer recipe itself.

What’s worse is that this can often be a bit of a gamble. Brut IPAs may be hot right now. Will they be hot a year from now? Uncertainty sets in and your mood darkens. Mystery abounds. “We can move 7,000 bbls of this, right?” Rather than risk rolling out a completely untested offering that may not land with beer drinkers, why not add a twist to an old favorite—maybe a different hop bill, different yeast strain, or some sort of seasonal adjunct?

By using your established brand’s name and reputation, you can lend that level of trust to the new beer, mitigate risk and achieve velocity sooner.

Brand Extensions

A brand extension is when you use your brand equity (the amount of goodwill, recognition and trust your customers have with your brand) to create a new product outside of your main category.

Example: A popular brewery opens a distillery under the same (or similarly themed) name. Or that same brewery uses its spent grain to make branded candles or dog treats. Here, you’re leveraging the weight of your parent brand itself to lend credibility the new product. The more established or respected your company, the more effective this will be.

One caveat—you generally want to stay within the same universe as your main category to achieve the best results. If you’re making the best beer in the state, then you could probably make some good whiskey too (from a customer perspective, anyway). If you make the best beer in the state but decide to use your brand name for a new boutique watch company, that might not compute with your customers. The qualities and promises that your parent brand offers should intuitively link to your new extension.

While it may sound like a brand extension is the perfect solution for growth, we need to mention a potential negative side effect. If your new extension isn’t well received, your parent brand’s reputation can suffer. Think of this like a referral. We’re all careful about who we refer to our family and friends (mechanics, lawyers, doctors, design firms) because the service they provide is a direct reflection on us. The friend you’re giving a referral to trusts you enough to listen to you. And if that mechanic doesn’t repair your friend’s car properly, that trust is damaged. Likewise, if that new product you put your brewery’s name on doesn’t live up to your standards, your customers can feel let down.

Co-branding

Co-branding is a strategic partnership between two companies—these can be in the same industry or completely different—to create a product that bears both of your names. It leverages the strength of each brand to create something cool and premium while introducing each company to the other’s customer base. It can also help you each achieve deeper market penetration within your own respective categories or tap into a new category altogether.

Some of these opportunities won’t result in a clear-cut ROI, but can instead be measured in the amount of positive brand equity, reputation and earned media you each generate. They can also be a fun way of doing something with friends or companies you respect or of raising money or awareness for a cause.

Example: Backward Flag Brewing co-brands special beer releases with various veteran-centered charities, raising money and awareness for them along the way.

Here are a couple of things to consider for deciding when and how to co-brand a product:

- A co-branding partnership should be with a company whose brand values align with your own.

- You’ll need to decide up front to what degree each entity’s branding will be featured on the new product.

- You need to agree on what type of ROI you each expect to receive from

the partnership.